How Working Parents Affect Family Life and Truancy

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Parental piece of work absence is associated with increased symptom complaints and school absence in boyish children

BMC Public Health volume 17, Article number:439 (2017) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Previous studies have proposed that having parents out of work may influence adolescent illness behaviour and school attendance. However, prior research investigating this question has been limited by retrospective reporting and example control studies. In a large epidemiological study we investigated whether parental work absenteeism was associated with symptom complaints and increased school absenteeism in adolescents.

Methods

We analysed information from a large epidemiological study of 10,243 Norwegian adolescents aged 16–nineteen. Participants completed survey at school, which included demographic data, parental work absence and current health complaints. An official registry provided school attendance information.

Results

Parental work absence was significantly related to the number of adolescent symptom complaints as well as school absence. Having a father out of work was associated with an increased likelihood of being in the highest quartile of symptom reporting by an odds-ratio of 2.2 and mother by 1.6 (compared to the lowest quartile). Similarly, parental work absenteeism was associated with an increased likelihood of being in the highest quartile for school absence by an odds-ratio of 1.ix for a father beingness out of work and ane.five for a mother out of work. We found that the number of adolescent symptom complaints mediated the relationship between parental piece of work absenteeism and school absenteeism.

Decision

We found that parental work absence was significantly associated with the number of adolescent symptom complaints and school absenteeism. The results suggest that parents may play a critical modelling role in the intergenerational transmission of illness and disability behaviour.

Background

A number of studies have speculated that parental sickness and work absenteeism (here defined as unemployment, sick leave or permanent work disability) may play a key function in influencing both adolescent symptom reporting and school absence. Several studies in the chronic hurting literature accept noted a relationship betwixt the beingness of parental pain models at domicile and the reporting of both hurting symptoms in young people and the disruption to their normal daily activities due to pain [one,two,3]. Having a parent with a hurting condition seems to put children at run a risk of increased illness behaviour and somatic complaints [4].

A like blueprint has been noted by clinicians and researchers working in the area of children's gastrointestinal complaints and unexplained pain. Here researchers have likewise noted a link between parental pain and symptom complaints and functional gastrointestinal symptoms or pain in their children [five, 6]. In an illustrative instance command written report, Campo and colleagues [7] compared mothers of eight–15 year children and adolescents presenting with unexplained abdominal pain to a command group of mothers presenting for routine care. The researchers found that compared to control mothers, mothers of children and adolescents with unexplained abdominal hurting were significantly more probable to have a history of irritable bowel syndrome, migraine and somatoform disorders, as well as accept been more frequent users of ambulatory health intendance services.

To engagement there has been little piece of work looking at the association between the impact of parental disease on children and, specifically, the role of parental piece of work absence on symptom complaints and school absence [8]. Interpretation of the results of previous studies in the expanse has been weakened by the use of retrospective reporting. In these studies participants were asked about their current symptoms and asked to remember whether parents had pain weather condition when they were growing up (e.g. (iii)). Other case control studies have drawn their sample from patients already in clinical intendance. Conspicuously, more data is needed from large population studies where information about adolescent symptoms and schoolhouse absence can be collected concurrently with parental work absence. In the electric current study we drew on a large general population survey of adolescents collected in Western Kingdom of norway to investigate whether parental work absence was associated with a greater level of symptom complaints in adolescence. A second aim was to explore if parental work absenteeism was associated with adolescent schoolhouse absenteeism and if this was mediated past adolescent symptom complaints.

Methods

Process and participants

In this population-based study from 2012, we used data from the youth@hordaland-survey of adolescents in the county of Hordaland in Western Norway. The general aim of the youth@hordaland-survey was to assess mental health, lifestyle, school performance and the use of wellness-service in adolescents. In collaboration with the Hordaland Canton, all adolescents built-in between 1993 and 1995 and all students attending secondary education were invited to participate. The adolescents received information nearly the written report via their official school e-postal service, and one school class (about 45 min during regular schoolhouse hours) was allocated for them to complete the Internet based questionnaire. A instructor was nowadays to organize the data collection and to ensure confidentiality. Those not attending school received the survey past mail posted to their dwelling address. Survey staff were available by telephone for both the adolescents and schoolhouse personnel to reply queries related to the research. The adolescents' parents were informed nearly the report, while the adolescents themselves consented to participating in the report, as Norwegian regulations state that individuals aged 16 years and older are required to provide their own consent. The study was approved by the Regional Commission for Medical and Health Research Ideals in Western Kingdom of norway. A full of 19,439 adolescents were invited to participate in the survey, of which 10,254 agreed, yielding a participation rate of 53%.

Measures

Sociodemographical characteristics

Gender and date of birth were identified through the personal identity number in the Norwegian National Population Register.

Parental piece of work absenteeism

Parental piece of work absence was defined by an open-ended question where the adolescents described their parents work status for mothers and fathers separately. This was coded according to ISCO-08 classification [ix]. Beingness in work was defined as parents with a work ISCO code or parents reported to be students (mothers, 8558). The out-of-work category consisted of parents that were not in piece of work (including parents on sick leave, inability pensions, as well as unemployed parents and homemakers (mothers, n = 594). Parents that were dead (mothers, north = 33; fathers, north = 55) or retired (mothers, n = 4; fathers, n = 64) were coded equally missing.

Adolescent symptom complaints

Symptom complaints were measured using v items, four from the HBSC-symptoms checklist [10]. Participants reported the frequency of headache, abdominal pain, back hurting, dizziness and pain in neck/shoulders, experienced during the last 6 months on a five-point calibration ranging from "more or less every day" to "seldom or never". The 5 items were summed to a total score (range 0–20), and and then divided in 4 categories past quartiles. In addition, a count variable was created summing the number of dissimilar symptoms the adolescents reported experiencing "weekly" or more than often (range 0–5).

Adolescent school absence

Non-omnipresence at schoolhouse over the past semester (6 months) was assessed using official annals-based information provided past Hordaland Canton Council. For the purpose of the present study, we used both the continuous variable (mean of days and hours), besides every bit categorical variables using the quartiles as cut-offs based on the continuous variable.

Statistics

IBM SPSS Statistics 22 for Mac (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill) was used for all regression analyses. Multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the predictive event of the parental work absenteeism (independent variables) on 1) increased symptom complaints and two) school absenteeism in the boyish children (dependent variables). Multinomial logistic regression analyses were likewise used to examine the clan betwixt number of weekly symptoms (independent variable) and level of school absenteeism (dependent variable).

In order to appraise whether boyish symptom complaints mediated the association betwixt parental work affiliation and school absenteeism, indirect effects analyses were conducted inside a structural equation modelling framework using version 0.5–16 of the Lavaan package [xi] in R for Mac version iii.1.one [12]. Maximum likelihood estimation with bootstrapped (k = m) standard errors and confidence intervals was used according to recent recommendations [13]. Incomplete responses were handled using pairwise deletion, ensuring high data retention in the analyses (92.6% in analyses with mothers and 88.four% in analyses with fathers).

Results

Parental work absenteeism and symptom complaints

Parental work absenteeism was significantly associated with increased symptom complaints in adolescent children. As detailed in Table 2, having a begetter that did not work was associated with an increased odds-ratio of 2.2 for reporting a symptom level in the 4th quartile (compared to the 1st quartile). A similar, but somewhat weaker effect was found for mothers not working (OR = 1.6). Parental work absenteeism was also associated with an increased odds of reporting less severe symptoms levels, with ORs of reporting symptom levels in in the 3rd quartile of i.4 for both mother and begetter non working (run into Tabular array i for details).

Parental work absenteeism and schoolhouse absence

Parental piece of work absenteeism was also significantly associated with increased school absence in adolescent children (Table 2). Having a father that did not piece of work was associated with an increased odds-ratio of 1.9 for having a schoolhouse absenteeism in the 4th quartile (7 days or more of school non-omnipresence). A like, but somewhat weaker effect was found for mothers not working (OR = 1.5). The associations were present for both days and hours of school absence (see Table 2 for details).

Adolescent symptom complaints and schoolhouse absenteeism

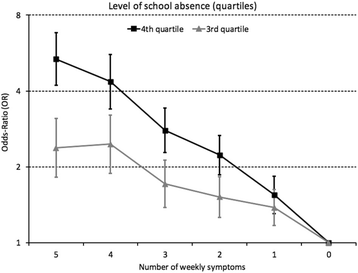

The number of weekly symptom complaints was associated with increased odds of schoolhouse absence in a dose-response style (Fig. 2). For example, compared to reporting no symptoms, having v unlike weekly symptoms increased the odds of substantial school absence (4th quartile) by 5.four, whereas reporting but 1 symptom was associated with an OR of i.five. A similar trend was found for absence in the third quartile (see Fig. one for details).

Weekly symptom complaints associated with school absence (third and 4th quartiles compared to 1st quartile) amongst adolescents in the youth@hordaland-study. Markers represent odds-ratios (OR) and mistake bars correspond 95% confidence intervals (Y-axis has a logarithmic calibration)

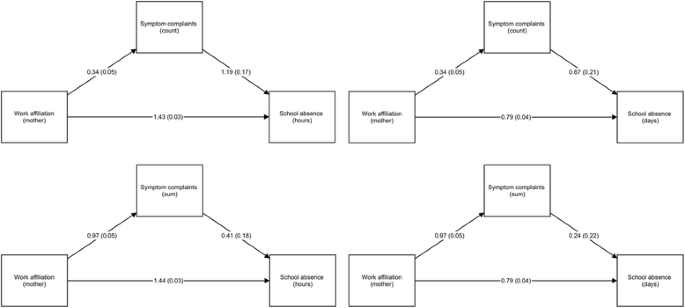

Symptom complaints as mediators of the association between parental work absenteeism and school absence

The relationship betwixt parental work affiliation and hourly absence from school was mediated by symptom complaints, as depicted in Figs. 2 and 3. In regression models, parental work absence was significantly associated with increases in school absenteeism and with increased symptom complaints, and symptom complaints were associated with school absence. Symptom complaints mediated 17–26% of the total effects on school absence, and the models explained two.5–5.3% of the variance in school absenteeism, see details in Table three.

Path models illustrating symptom complaints (equally sum/count) acting as a mediator of the association betwixt maternal work amalgamation and schoolhouse absenteeism (in hours/days). Unstandardized coefficients and standardized coefficients (in parenthesis) shown

Path models illustrating symptom complaints (as sum/count) acting as a mediator of the clan betwixt paternal work affiliation and schoolhouse absenteeism (in hours/days). Unstandardized coefficients and standardized coefficients (in parenthesis) shown

Give-and-take

The findings in the present study from a general population study of Norwegian adolescents evidence that parental work absence was significantly associated with both the number of boyish symptom complaints and schoolhouse absence. While co-occurring adolescent symptom complaints deemed for some, only not all of this clan, a arbitration analysis confirmed both a directly and significant indirect effects via adolescent symptom complaints on their schoolhouse absenteeism.

The results advise a stiff interrelation between parents and boyish absence behavior, also the importance of health complaints in understanding this clan. The results confirmed our hypothesis of parental work absence being associated with both symptom reports and school absenteeism in the adolescents. The association between parental and adolescents school absence in relation to wellness complaint is in line with previous reports from clinical studies apropos the clan between symptom complaints and responses to wellness complaints among parents and children [1, 2]. A previous register-based study also found an increased risk of laurels of inability pension among immature adults among parents who are outside the workforce [xiv]. The clan between parental work affiliation, and boyish health complaints and school absence may thus be one pathway that tin can account for the intergenerational transmission of disability pension.

From a theoretical perspective, social learning theory may be a useful conceptual framework to understand these associations. Social learning theory posits that learning occurs through observation and vicarious reinforcement of others [15]. In this case, health complaints and school absence in the adolescents may be perceived as a possible response when observing parents with like attributes and behaviors [16]. As such, it is likely that having a parental role model that is not working may be an important contributing factor for the reported symptom complaint and school absenteeism behavior. From this perspective, absence from work life and school may also be viewed every bit affliction behavior or a coping mechanism in response to health complaints that is learned by adolescents. The intergenerational manual of affliction beliefs that is described in the clinical literature may give the states a framework to understand these results [5]. The present study is an epidemiological report that is restricted from describing the internal familial processes that contribute to wellness complaints and school absence in families with parents out of the piece of work force. Other potential pathways may also be at work. Adolescent stress or mental health problems may besides exist related to both the health complaints and schoolhouse absenteeism, and may thus constitute alternative contributing factors [17].

Some researchers have hypothesized that parental influence on adolescents may exist less in the late adolescents years, when peers influence exerts more than influence [xviii]. Others have advocated a family perspective and-intergenerational perspective to understand the association betwixt health and educational attainment [19], as well as the intergenerational transmission of both wellness and work affiliation. The associations between parental work absenteeism and both symptom written report and school absence in the present study lends support from the family unit perspective and suggest the continuing potent influence of parents in this historic period group.

Somatic complaints are frequent during adolescence and associated with a loftier rate of school absence. This is in line with the functional impairment of somatic complaint in adults, known to be one of the most frequent causes of works absenteeism [xx]. We know that health complaints increase during adolescence and become more settled in adulthood [21]. Thus the functional damage in relation to somatic adolescent complaints may also be a risk factor maintaining a stable futurity work amalgamation and the adoption of future disability payments.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of the study is the apply of data from administrative registries on school absence and thus reducing the run a risk of the bias inherent in a uncomplicated informant. There are limitations that should be noted. Starting time, parental absence was based on adolescent report and is thus non confirmed by registries, and nosotros do not have information on the parents' wellness status. Second, response rate could bear on generalizability. Based on previous research from the erstwhile waves of the Bergen Kid Study, not-participants have been shown to have more than psychological problems than participants [22], and information technology is therefore possible that the level of symptom complaints may exist underestimated in the current written report. The mean GPA for the participants were non significantly different from the national mean GPA [22]. Thirdly, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow for causal inferences, and future studies should investigate if the associations between parental work affiliations and co-occurring school absence will be related to future work amalgamation for the adolescents entering adult life, and if the symptom complaints may also explain these associations.

Finally, due to restrictions in statistical ability we could not clarify girls and boys separately, and future studies should examine if there at gender specific patterns of clan, every bit has been suggested in studies of early disability when the parent of ones one gender was disabled. [14] Finally, the explained variance of the model is relatively pocket-size, and indicates that this is just one of many factors that are related to school absence. Other factors known to be associated with school absence such equally for case sleep problems [23] and booze and drug use [24] may besides be of importance and were not addressed in the current study.

Conclusions

In the present study we found parental work absence was significantly associated with the number of adolescent symptom complaints and schoolhouse absence. The results suggest that parental work models may play a critical role in the intergenerational transmission of illness and disability behaviour. One of the implications of strengthening the understanding of parental influences on both health and school functioning, is the inclusion of a family perspective when health and school personnel meet adolescencents with health complaints and school absenteeism behavior. While the older adolescence is a transitional menstruum with college degree of independence, the parents still exerts important influence and should be included in interventions.

Abbreviations

- BCS:

-

Bergen Child Study

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

References

-

Evans S, Keenan TR, Shipton EA. Psychosocial adjustment and physical health of children living with maternal chronic pain. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007;43(4):262–70.

-

Lester N, Lefebvre JC, Keefe FJ. Pain in young adults: I. Relationship to gender and family pain history. Clin J Pain. 1994;10(4):282–ix.

-

Edwards PWZ, A, Kuczmierczyk AR, Boczkowski J. Familial pain models: the relationship between family history of hurting and current hurting experience. Pain 1985;21(iv):379–384.

-

Mikail SF, von Baeyer CL. Pain, somatic focus, and emotional adjustment in children of chronic headache sufferers and controls. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31(1):51–ix.

-

Levy RL. Exploring the intergenerational transmission of illness behavior: from observations to experimental intervention. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41(2):174–82.

-

Osborne RB, Hatcher JW, Richtsmeier AJ. The role of social Modeling in unexplained pediatric hurting. J Pediatr Psychol. 1989;14(ane):43–61.

-

Campo JV, Bridge J, Lucas A, Savorelli Due south, Walker L, Di Lorenzo C, et al. Concrete and emotional health of mothers of youth with functional abdominal pain. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(2):131–seven.

-

Korneluk YG, and Catherine K. Lee. Children'south adjustment to parental physical illness. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 1998;i(3):179–193.

-

International Labour Office. International standard classification of occupations: ISCO-08. Volume ane. Construction, group definitions and correspondence tables. Geneva: International Labour Office; 2012.

-

Haugland S, Wold B. Subjective health complaints in boyhood--reliability and validity of survey methods. J Adolesc. 2001;24(v):611–24.

-

Rosseel Y. Lavaan: an R package for structural equation Modeling. J Stat Softw. 2012;48(2):one–36.

-

R Core Squad. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013.

-

Hayes AF. Across baron and Kenny: statistical arbitration analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr. 2009;76(4):408–20.

-

Gravseth HM, Bjerkedal T, Irgens LM, Aalen OO, Selmer R, Kristensen P. Life course determinants for early on disability pension: a follow-up of Norwegian men and women born 1967-1976. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22(8):533–43.

-

Bandura A. Social learning theory of aggression. Aust J Commun. 1978;28(3):12–29.

-

Faasse K, Petrie KJ. From me to you: the effect of social Modeling on treatment outcomes. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2016;25(6):438–43.

-

Egger HL, Costello EJ, Angold A. School refusal and psychiatric disorders: a community report. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(vii):797–807.

-

West P. Health inequalities in the early on years: is there equalisation in youth? Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(half dozen):833–58.

-

De Ridder KAA, Pape One thousand, Johnsen R, Holmen TL, Westin S, Bjorngaard JH. Adolescent wellness and high school dropout: a prospective cohort report of 9000 Norwegian adolescents (the immature-Hunt). PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74954.

-

Waddell Thou, Burton One thousand, Aylward G. Work and mutual health problems. J Insur Med. 2007;39(2):109–20.

-

Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO, Manniche C. The form of depression back hurting from adolescence to adulthood: eight-twelvemonth follow-upwardly of 9600 twins. Spine. 2006;31(iv):468–72.

-

Stormark KM, Heiervang Eastward, Heimann Chiliad, Lundervold A, Gillberg C. Predicting nonresponse bias from instructor ratings of mental health problems in primary schoolhouse children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2008;36(3):411–9.

-

Hysing M, Haugland S, Stormark KM, Bøe T, Sivertsen B. (2015). Sleep and school omnipresence in adolescence: results from a large population-based study. Scand J Public Wellness. 43(1):ii–9.

-

Henry KL, Thornberry TP. Truancy and escalation of substance use during adolescence. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71(1):115–24.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Regional Centre for Child and Youth Mental Health and Child Welfare at Uni Enquiry Health and the Bergen Kid Report for collecting the data and making the data available for this report. The authors would also like to give thanks the participants for their time and effort.

Funding

The study was funded by Uni Research Wellness and Norwegian Directorate for Wellness and Social Affairs the Norwegian Research Council project number 228189.

Availability of information and materials

With regards to making the data available; Norwegian Health research legislation and the Norwegian Ethics committees crave explicit consent from participants in order to transfer wellness inquiry information exterior of Norway. In this specific case, ethics approval is also contingent on storing the inquiry data on secure storage facilities located in our inquiry institution. Data are from the Norwegian youth@hordaland-survey whose authors may be contacted at bib@uni.no.

Authors' contributions

Author MH, BS and TB were involved in conquering of data. Authors BS, KP, TB and MH were responsible for conception and design of the study, conducted the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. Authors MH, BS, KP and TB gave critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Authors BS and MH had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibleness for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the information analysis. All authors read and approved the concluding manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they accept no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accord with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research commission and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable upstanding standards.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The adolescents' parents were informed almost the report, while the adolescents themselves consented to participating in the study every bit Norwegian regulations country that individuals aged sixteen years and older are required to provide consent themselves. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Enquiry Ethics in Western Kingdom of norway.

Publisher's Notation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Affiliations

Respective writer

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution iv.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/), which permits unrestricted utilize, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided y'all give appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons license, and betoken if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/nix/1.0/) applies to the data made bachelor in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Near this article

Cite this commodity

Hysing, 1000., Petrie, K.J., Bøe, T. et al. Parental work absenteeism is associated with increased symptom complaints and schoolhouse absence in adolescent children. BMC Public Health 17, 439 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4368-7

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4368-7

Keywords

- Schoolhouse attendance

- Symptom complaints

- Adolescence

- Parental work absence

Source: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-017-4368-7

0 Response to "How Working Parents Affect Family Life and Truancy"

Publicar un comentario